| VietnamJournal Login |

|

If you do not have an account yet Create

One. | |

|

VietNam Journal |

VietNam Journal is an online

quarterly magazine. The magazine is created to serve as

a forum for students and scholars to present

disciplinary and interdisciplinary research findings on

a broad range of issues relating to Vietnam and

Vietnamese overseas. VietNam Journal embraces the

diversity of both academic interests and scholastic

expertise. It is hoped that this forum will introduce

scholars to the work of their colleagues, encourage

discussion both within and across disciplines, and

foster a sense of community among those interested in

Vietnam. VietNam Journal welcomes you to its issues.

Crucial to the success of this publication is your

involvement. VietNam Journal wishes to receive your

input, your criticisms, and your contributions. Please

help us in this challenging

endeavor! | |

| Copyright & Disclaimer Notice |

Copyright:

All electronic

documents available on VietNam Journal are, unless

otherwise noted, the copyright of the authors and/or the

organization sponsoring the documents. Permission to

reproduce or publish copyrighted text or images must be

obtained from Vietnam Journal and the copyright holder.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in

VietNamJournal are solely those of the authors and do

not represent the views of VietNamJournal or its

editors. Questions, comments, and original contributions

should be addressed to the Board of

Editors.

| |

|

The Present

Echoes of the Ancient Bronze Drum:

Nationalism and

Archeology in Modern Vietnam and China

by:

Xiaorong Han on: Tuesday 21 August @ 23:53:48 |

by Xiaorong

Han |

| Introduction |

? |

Bronze drums are one of the most important archaeological

artifacts to be found in southern China and Southeast Asia.

Their use by many ethnic groups in that area has lasted from

pre-historical times to the present. Northern Vietnam and

southwestern China (especially Yunnan Province and the Guangxi

Zhuang Autonomous Region) are the two areas where the majority

of bronze drums have been discovered. According to a 1980

report, China has stored about 1460 bronze drums.[1] The

Provincial Museum of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region

actually boasts the largest collection of Bronze drums in the

world. The total number of bronze drums discovered in Vietnam

reached about 360 in the 1980s, among which about 140 were

Dong Son drums.[2]

The earliest historical records about bronze drums appeared

in the Shi Ben, a Chinese book written in the 3rd century BC

or earlier. The book is no longer extant, however a small

portion of it appears in another classic, theTongdian by Du

You.[3] The Hou Han Shu, a Chinese chronicle of the late Han

period compiled in the 5th century AD, describes how the Han

dynasty general Ma Yuan collected bronze drums from Jiaozhi

(northern Vietnam) to melt down and then recast into bronze

horses. From that point on, many official and unofficial

Chinese historical records contain references to bronze drums.

In Vietnam, two 14th century literary works written in Chinese

by Vietnamese scholars, the Viet Dien U Linh and the Ling Nam

Chich Quai, record many legends about bronze drums. Later

works such as the Dai Viet Su Ky Toan Thu, a historical work

written in the 15th century, and the Dai Nam Nhat Thong Chi, a

book about the historical geography of Vietnam compiled in the

late 19th century, also have records about bronze drums.[4]

Further, there is also a wooden tablet from the early 19th

century found in Vietnam which describes the discovery of some

bronze drums.[5]

Modern archaeological research on the bronze drum did not

begin until the late 19th century, after the arrival of

Westerners in the region. Before the 1950s, almost all of the

important works on the bronze drum were written by western

scholars. Notable works from this period are F. Heger's Alte

metalltrommeln aus Sudost Asien (Leipzig, 1902), F. Hirth's

Alte bronze Pauken aus Ostasien (Vienna, 1891), A.B. Meyer and

W. Foy's Bronze-Pauken aus Sudost-asien (Dresden, 1897), and

B. Karlgren's The Date of the Early Dong-son Culture (Bulletin

of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, 1942).[6] Due to the

social-political circumstances, few Vietnamese scholars were

able to engage in research on the bronze drum during those

years. In China, a monograph entitled Tonggu kaolue (A Brief

Introduction to the Bronze Drum), written by Zheng Shixu, was

published in Shanghai in 1936. Although some famous Chinese

scholars, such as the historians Xu Songshi and Luo Xianglin,

also showed interest in the bronze drum, no other significant

Chinese works on bronze drums were produced during that

period. ?

After the establishment of the PRC in 1949 and the division

of Vietnam in 1954, Vietnamese and Chinese scholars began to

dominate research on the bronze drum. In the 1950s and 1960s,

many excavation reports and some general studies on the bronze

drum were published. However, on the whole, the bronze drum

did not attract serious attention in either country. Moreover,

although China and Vietnam maintained good bilateral relations

during that period, very little academic exchange took place

between the bronze drum experts from the two countries. It was

not until the mid-1970s, shortly before the break-up of the

Sino-Vietnamese alliance, that several important articles

began to be published in both countries. The late 1970s and

early 1980s then saw the publication of many more books and

articles on the topic in both China and Vietnam, and heated

debates between Vietnamese and Chinese scholars ensued. In

March 1980, the first Chinese symposium on the ancient bronze

drum was held in Nanning, the capital city of the Guangxi

Zhuang Autonomous Region in southern China. The Chinese

Association for Ancient Bronze Drum Studies was formed

immediately following the conference. Another symposium was

held in Kunming, the provincial capital of Yunnan Province, in

late 1984.[7] In 1987, Vietnamese scholars summed up their

views in a book called Trong Dong Son (The Dong Son Drum).[8]

The following year, the Chinese Association for Ancient Bronze

Drum Studies (ZGTY) also completed a conclusive monograph

entitled Zhongguo Gudai Tonggu (The Ancient Bronze Drums of

China). In October 1988, Vietnamese and Chinese archaeologists

finally met at the International Symposium on The Bronze Drum

and Bronze Culture of South China and Southeast Asia to

discuss their differences. The publication of the

above-mentioned two books and this symposium actually put an

end to the protracted controversy. Since then, no important

works on the bronze drum have been published in either Vietnam

or China.

The timing of this Vietnamese and Chinese research on the

bronze drum indicates much about its political implications.

The recent boom in bronze drum research started when

Sino-Vietnamese friendship was about to turn sour, and it

ended when the two countries were ready to seek a solution for

their problematic relations. The political influence on

research is also reflected in the issues that the Vietnamese

and Chinese archaeologists chose to address in the 1970s and

1980s. While in the previous period, scholars had tended to

give more or less equal attention to the classification,

dating, origin, functions, and other issues relating to the

bronze drum, in the 1970s and 1980s, scholars paid much more

attention to the geographic and ethnic origins of the bronze

drum than to other issues. Where the first bronze drum was

made and who made it were the core issues in the controversy

between Chinese and Vietnamese scholars during that period.

The answers to these questions seem to have been largely

determined by the nationality of the schola?s concerned. Hence

the Vietnamese scholars unanimously claimed that the bronze

drum was invented in the Red and Black River valleys in

northern Vietnam by the Lac Viet, the remote ancestors of the

Vietnamese people, and then spread to other parts of Southeast

Asia and southern China. Meanwhile, Chinese archaeologists

declared that the real inventor of the bronze drum was the Pu,

an ancient ethnic group who inhabited southern China. Chinese

scholars argued that the Pu first made the bronze drum in

central Yunnan in southwestern China, and that the technique

was then adopted by other ethnic groups living in the

surrounding areas, including the Lac Viet in the Red River

delta.

In this article, I intend to make a brief review of the

major works on the bronze drum published in Vietnam and China

in the 1970s and 1980s, and will demonstrate how nationalism

predetermined the positions of the scholars researching the

issue of the origin of the bronze drum. I will also discuss

how their theories about the origin of the bronze drum in turn

influenced their understanding of other aspects of the bronze

drum, such as its typology, dating and decoration. My chief

concern here is not to prove which side is right or wrong, but

to try to explain why the issue of the origins of the bronze

drum became so important to the Vietnamese and Chinese

scholars during this period, and why no scholars expressed

different views from those of their compatriots. |

| Classification and Dating |

|

The most well-known classification of the bronze drum was

made by the Austrian archaeologist F. Heger in 1902 in his

Alte metalltrommeln aus S?Asien. He collected 22 bronze drums

and the records or photographs of another 143, which he

divided into four types (I, II, III, IV) and three transitory

types (I-II, II-IV, I-IV) based on their form, distribution,

decoration and chemical composition. He believed that Type I,

or the Dong Son drum, as the Vietnamese scholars prefer to

call it, which had mostly been found in northern Vietnam by

that time, was the earliest.[9] Before the 1950s, some other

classifications were proposed, but none of them were as widely

adopted as Heger's.

Did Heger's classification stand the test of time and the

excavation of many more bronze drums? Vietnamese scholars

thought that the general framework of Heger's classification

was still valid, that it could be modified or expanded, but

should not be replaced. Since they continued to use Heger's

general framework, Vietnamese scholars did not expend any time

on working out new schemes. Instead, they chose to concentrate

on the details, with the aim of further proving Heger's

classification with new evidence discovered after 1902, and

defending him from Chinese attacks. With many more bronze

drums in hand, they began to divide each of Heger's types into

several sub-types. They focused their efforts on Heger's type

I, namely, the Dong Son drum, believed to be t?e earliest of

the various types of bronze drums and which had been mainly

found in northern Vietnam. For example, In 1963, Le Van Lan,

Pham Van Kinh and Nguyen Linh proposed to subdivide Heger's

type I according to the proportion between the diameter of the

face and the height of the drum. In 1975, Nguyen Van Huyen and

Hoang Vinh subdivided Heger's Type I into three subtypes. In

the same year, in an article published in Nhung Phat Hien Moi

Ve Kao Co Hoc (the New Archaeological Discoveries), Pham Van

Kinh and Quang Van Cay suggested that Heger's type I be

subdivided into seven subtypes belonging to four consecutive

stages.[10] Tran Manh Phu[11] and Luu Tran Tieu and Nguyen

Minh Chuong[12] subdivided it into four subtypes. Chu Van

Tan[13] proposed two subtypes with five transitory types. Di

ep Dinh Hoa and Pham Minh Huyen[14] suggested seven subtypes.

However, the most complicated scheme was proposed by Pham Minh

Huyen, Nhuyen Van Huyen and Trinh Sinh, who divided Heger's

Type I into six subtypes with 24 styles.[15]

Vietnamese scholars paid much more attention to the Dong

Son drum than to the other types of bronze drum that Heger had

identified. They saw these other types as later in date and

thus less related to the Vietnamese people.[16] Therefore,

they were much less important than the Type I drums for

proving the Vietnamese origin of the bronze drum.

The attitude of Chinese archaeologists toward Heger's

classification is sharply contrasted with that of Vietnamese

scholars. They believed that Heger's classification was so

outdated that it necessitate a complete overhaul. After the

break-up of bilateral relations, Chinese scholars began to

openly criticize Vietnamese scholars for what they saw as

blind adherence to Heger's classification for unacademic

reasons. As one Chinese book put it, Heger could be forgiven

for asserting that the Dong Son drum was the earliest because

he did not have enough evidence at that time, but Vietnamese

scholars could not be forgiven because they had so much more

information than Heger, but still refused to pay due attention

to this new evidence.[17]

From the 1950s to the 1980s, Chinese scholars strove

continuously to make new schemes of classification. In total

they made at least seven schemes during those four decades.

From the 1950s to the mid 1970s, the Chinese scholars

endeavored to reverse the order of Heger's first three types

by categorizing the type II as the earliest, and arguing that

Heger's type I developed from the type II. Three out of four

classifications made by Chinese scholars during that period

did precisely that.[18] Only the Yunnan Provincial Museum[19]

continued to support Heger's order. The above modifications of

Heger's classification naturally led to much suspicion from

the Vietnamese side. Vietnamese scholars were aware that China

had very few of Heger's type I bronze drums at that time, and

that the great majority of Heger's type II drums had been

discovered in Guangxi in southern China.

By the mid to late 1970s, Ch?na had discovered many bronze

drums believed to belong to Heger's Type I. Moreover, after

the excavation of Wanjiaba in Yunnan Province in 1975-1976,

Chinese archaeologists believed that they had found the most

archaic form of Heger's type I bronze drum. As a result, they

began to discard the schemes made by Chinese archaeologists in

the previous period and to go back to Heger's classification.

Here, however, they made one important modification: they

added the newly-found Wanjiaba drums to Heger's plan as the

earliest type. Wang Ningsheng,[20] Li Weiqing[21] and Shi

Zhongjian[22] represented this new revisionist school. This

revisionist school maintained the earlier Chinese view that

southern China was the place of origin of the bronze drum, yet

in their works they differed greatly from the previous

classifications in that they took Yunnan, instead of Guangxi,

as the specific place of origin of the bronze drum within

southern China. This indicated some differences between the

Chinese scholars in Guangxi and their colleagues in Yunnan.

These differences were not new, considering that among the

four classifications made by Chinese scholars between the

early 1950s and the mid-1970s, only the one made by the Yunnan

Provincial Museum refused to recongnize Heger's type II, which

was found mostly in Guangxi, as the earliest bronze drum. It

was probably not a coincidence that two of the three scholars,

Huang Zengqing and Hong Sheng, who claimed the Guangxi origin

of the bronze drum were from Guangxi, the other, Wen You,[2 3]

hailing from the neutral ground of Sichuan. Incidentally, two

of the scholars who claimed the Yunnan origin of the bronze

drum, Wang Ningsheng and Li Weiqing, were from Yunnan, the

other, Shi Zhongjian, coming from the neutral ground of

Beijing. It was reported in 1982, however, that a majority of

Chinese archaeologists had agreed that the bronze drum

originated in Yunnan (Shi Zhongjian 1982:203).[24] This

implied that there was still a minority that did not agree.

The debate with Vietnamese scholars had probably prevented

this minority from expressing their views. By 1995, it was

finally announced that Chinese archaeologists had all agreed

that the Wanjiaba type bronze drum was the earliest in the

world and that Chuxiong prefecture in Yunnan, where Wanjiaba

is located, is thus the birth place of the bronze drum.[25]

|

|

|

|

The Chinese modifications on Heger's classification:

|

| Author |

Classification |

Year |

| Heger |

|

I |

II |

III |

IV |

1902 |

| Wen You |

|

II (western) |

I (eastern) |

|

III |

1957 |

| Yunnan Museum |

|

I |

II |

|

III |

IV |

1959 |

| Huang Zengqing |

|

II |

III |

I |

IV |

1964 |

| Hong Sheng |

|

III |

II |

I |

IV |

1974 |

| Wang Ningsheng |

A |

B |

C |

D |

F |

E |

1978 |

? | Li Weiqing |

I:a |

I:b |

I:c |

II:a |

II:b |

III:a |

III:b |

1979 |

| Shi Zhongjian* |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

5 |

1983 |

| ZGTY |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

5 |

1988 | |

*One way to bolster

their claims about the origins of the bronze drum was to name

each type of bronze drum after the name of the place where it

was found. Just as Vietnamese scholars preferred to use

Vietnamese place names to name the bronze drum (for example,

the Dong Son drum), Chinese scholars also liked to use Chinese

place names in their classifications. For example, Shi

Zhongjian and the Chinese Association for Ancient Bronze Drum

Studies chose the following Chinese place names to designate

their eight types of bronze drum: 1. Wanjiaba (Yunnan); 2.

Shizhaishan (Yunnan); 3. Lengshuichong (Guangxi); 4. Zunyi

(Guizhou); 5. Majiang (Guizhou); 6. Beiliu (Guangxi); 7.

Lingshan (Guangxi); 8. Ximeng (Yunnan). The conclusive volume

edited by the Chinese Association for Ancient Bronze Drum

Studies (ZGTY) followed Shi Zhongjian's classification. Shi

was the director of the Board of Directors of the Association

at the time of writing and he also wrote the preface to the

volume.

Vietnamese scholars claimed that the attempts by Chinese

archaeologists to reclassify the bronze drums were all

groundless. They argued that besides the fact that China had

very few of Heger's type I drums, the Chinese had reversed the

order of Heger's first three types before the mid-1970s

because they believed that the bronze culture in the south

could not have developed without the influence of Chinese

culture from the north. Heger's type II, the Vietnamese noted,

had something which the Chinese were looking for: decorations

similar to those found in the Central Plain area of China.

These classifications, just like the widespread belief in

premodern China that the bronze drum had been invented by Ma

Yuan, the Han general who crushed the Trung sisters' rebellion

in Vietn?m in 40 AD, and Zhuge Liang, the famous prime

minister of the state of Shu during the Three Kingdoms period

(220-265 AD),[29] reflected the mentality of Han chauvinism.

To Vietnamese scholars, Chinese influences were not

indications of an earlier date, but precisely the

opposite.[30]

The more recent Chinese classifications, which returned to

Heger's plan but added the Wanjiaba drums as the earliest

type, were based in part on the idea that the form and

decoration of the Wanjiaba drums were very simple, and the

premise that the simpler the form and decoration, the more

archaic the drum would be. Vietnamese scholars believed that

this was another misinterpretation. The three principles used

by Chinese scholars in their classification, namely, that "the

face of the drum grew bigger and bigger, the body of the drum

decreased from three to two parts, and the decorations became

more and more complex," were considered to be

oversimplifications by Vietnamese scholars. They argued that

the simple form and decorations could also be indications of

decline, thereby implying that the Wanjiaba drum was not the

earliest of the various types of bronze drum, but the

latest.[31] Phan Huy Thong was another Vietnamese scholar who

argued this point. According to him, drums of the same type

were found in Vietnam during the 1930s and had long since been

judged to be coarse but late.[32] Thus, in the most

complicated Vietnamese classification proposed in Pham Minh

Huyen et al. 1987, the Wanjiaba Drum was listed as the fourth

subtype of the Dong Son Drum (Heger's type I). The Thuong Nong

drum, a Wanjiaba style bronze drum found in Vietnam in the

1980s, was put in the same subtype (see figure I).

The aim of all of these classifications was to determine

the relative dating of the bronze drums. To date, scholars in

the two countries have not found common ground on this issue.

The biggest problem concerns the first two types of Heger's

classification, which are directly linked to the issue of the

origins of the bronze drum. Since relative dating proved

unconvincing to both sides, Chinese and Vietnamese scholars

then made attempts at absolute dating. However, this proved to

be as controversial as relative dating.

The Vietnamese scholar Vu Tang proclaimed in 1974 that he

dated one bronze drum to the 13th-10th centuries BCE and

another one to the beginning of the late second millenium BCE.

This is the earliest absolute dating so far proclaimed for any

bronze drum by any scholar. However, this dating later led to

much criticism from Chinese scholars, according to whom the

method used to date those two drums had been unscientific.[33]

The dating of the first drum was based on the motifs of rings

and parallel lines, which are believed to be similar to those

found on ceramics of that period of time. Apparently,

Vietnamese scholars later discarded this dating scheme, as it

was not included in Trong Dong Son (The Dong Son Drums), the

conclusive volume edited by Pham Minh Huyen et al., and

published in 1987.

? Other Vietnamese scholars believed that the earliest Dong

Son drum can be dated alternately to the 7th century BCE;[34]

or the 8th century BCE;[35] or sometime before the 7th century

BCE.[36] Vietnamese scholars later admitted that it was

difficult to reach an exact date for the Dong Son drum because

many drums were discovered accidentally, and thus, the sites

were not well protected. Further, it is very difficult to find

any biological materials that are directly related to the drum

to get an absolute date.[37]

The earliest C14 date established for a bronze drum

excavated in China by Chinese scholars is 2640+- 90 before

1950, or 690 +- 90 BCE.[38] The dating was based on the

materials that coexisted with the drum in the tombs. Chinese

scholars claimed that this is the earliest credible C14 dating

for any bronze drum. They argued that the Wanjiaba type bronze

drums were mostly made between the 7th and 5th centuries BCE,

and that the Shizhaishan (or Dong Son) type was popular

between the 6th century BCE and the 1st century AD, and that

the latter was a more developed form of the former (Wang Dadao

1990:536;540).[39] However, according to Vietnamese scholars,

this dating is erroneous. Vietnamese archaeologists conducted

an experiment on a piece of wood obtained from an excavated

coffin and found that the margin of error for such dating

could be as much as 235 years. They believed that the Chinese

archaeologists deliberately chose that date in order to

support their claim about the southern China origin of the

bronze drum. According to Vietnamese scholars, the dating of

bronze drums should not be based solely on C14 statistics, but

instead, that other factors should also be taken into

consideration. They even went so far as to set an example for

the Chinese. A bronze drum was found in an ancient tomb at

Viet Khe. C14 dating indicated that the tomb was from

2480+-100 years before 1950AD, or around 530 BCE. However,

based on its style, it was decided that the drum could only be

dated to the 3rd or 4th centuries BCE.[40] To date, scholars

from the two count ries have failed to reach common ground

regarding absolute dating, just as they have not achieved a

consensus on relative dating. |

| Interpretation of the

Decoration |

|

The decoration of the bronze drum is another major field of

controversy between Vietnamese and Chinese scholars.

Decoration is important because it is believed to reflect the

social and spiritual life of the people who invented and used

the drum, and thus, can help determine its ethnic and

geographical affiliations. The most popular motifs on the

early drums (Heger's first two types plus the Wanjiaba)

include various species of birds and other animals, as well as

boats, shining entities, and geometrical lines.

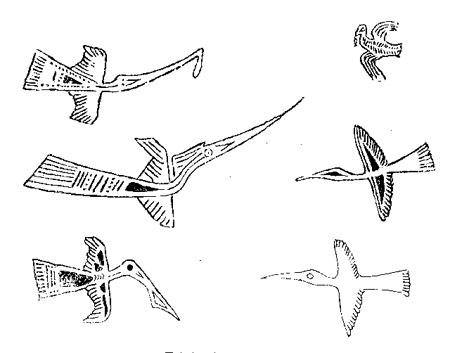

A flying bird with a long beak and long feet appeared very

frequently on the early drums, and a good deal of scholarly

attention was devoted toward ?rying to determine what kind of

bird it was. Dao Duy Anh, the Vietnamese historian, believed

that it was the legendary "lac bird," the symbol of the

ancient Viet people.[41] Dao Tu Khai, however, argued that the

bird was not a lac bird because the lac bird was a magpie or

some other species whose appearance was rather different from

that of the bird on the bronze drum . According to Dao Thu

Khai, the bird was instead a heron.[42] Still other scholars

argued that the lac bird and the heron were the same.[43] What

is more, it was argued that herons lived in every part of

Vietnam, and the ancient Viet people regarded it as the symbol

of the laborious peasants because it was believed to be

diligent. As one Vietnamese scholar put it, " We believe that

since the bronze drum is a product of Vietnam made by the Viet

people, it should reflect something real in the Vietnamese

landscape. The flying bird on bronze drums should be something

that the Viet people were very familiar with, and it should

have a Vietnamese name. We believe that our interpretation of

the bird with its long beak and long feet on bronze drums as a

heron is in conformity with the reality of Vietnamese history

and culture.[44]"

Some western scholars have also suggested a connection

between this and other birds on the bronze drum and the

Vietnamese identity, however they base their argument on a

different logic. For example, according to Taylor (1983:7;

313), the motifs of sea birds and amphibians surrounding boats

bearing warriors gave visual form to the idea of an aquatic

spirit as the source of political power and legitimacy, which

is the earliest hint of the concept of the Vietnamese as a

seaborne, distinct, and self-conscious people.[45]

Figure III: Flying Birds on Bronze Drums[46]

Most Chinese scholars also believe that the bird is a

heron. However, they do not agree that the heron is a symbol

of the ancient Vietnamese peasants. Instead, they interpret it

more as a result of Chinese influence. They argued that the

heron is considered to be the spirit of the drum in the

Central Plain of China. This belief first spread to the Chu

area in southern China and then reached other ethnic groups

living to the south of Chu. According to the Chinese

Association of Bronze Drum Studies, "The flying heron is the

major motif onShizhaishan drums (Dong Son drums). There is a

long tradition of decorating drums with the motif of herons in

the Central Plain. The feather drums excavated from the Chu

tombs in Xinyang, Henan and Jiangling, Hubei and the Zenghouyi

tomb in Suixian, Hubei are all decorated with the motif of the

heron...there is clear evidence to support the idea that the

motif of the flying heron on the Shizhaishan drums originated

in the Chu area."[47]

Figure IV: Frogs or toads on a Dong Son drum[48]

?

In addition to the bird motifs, there are also small

three-dimentioned animals on the face of some Dong Son

(Shizhaishan) drums and other types of drums which

archaeologists had argued are either frogs or toads. Chinese

scholars argued that they were frogs and explained them as

decorations without special meaning,[49] or something related

to the ceremony of rain-seeking, or the frog-worshipping

custom, of the ancient Yue people of southern China, a group

believed to be related to the ancient Viet people.[50] Edward

Schafer (1967:254) agreed that the animals were frogs, "for

the drum embodied a frog spirit--that is a spirit of water and

rain--and its voice was the booming rumble of the bullfrog."

He retold a story of the Tang period recorded in a Chinese

source to show that the drum could even take the form of a

living frog. According to the story, a frog pursued by a

person leaped into a hole, which turned out to be the grave of

a Man (barbarian) chieftain containing a bronze drum with a

rich green patina, covered with batrachian figures. The bronze

drum was believed to be the reincarnation of the frog.[51]

Vietnamese scholars initially agreed that the animals were

frogs in the 1970's,[52] but later interpreted them as toads

because "a widely known popular saying in Vietnam calls the

toad 'the uncle of the heavenly god' and maintains that rain

will inevitably fall when the toad raises his head and

croaks." [53]

Figure V: Boats on bronze drums[54]

The motif of a long boat is another very popular decoration

on the surface of the Dong Son (or Shizhaishan) drums. Usually

the two ends of the boat are decorated with the head and tail

of a bird. In the boat are numerous ornamented human figures.

There are fish under the boat and birds around the boat.

Following Goloubew, Dao Duy Anh believed this was the "golden

boat" described in the belief system of the Dayak people of

Kalimantan in Indonesia that carries the spirits of dead

people to heaven, which is in turn symbolized by the birds. He

further concluded that there was a possible blood relationship

between the Dayaks and the Lac Viet, and that the ancient Lac

Viet could be the ancestors of the Dayaks.[55]

Feng Hanji, a Chinese archaeologist, did not agree. He

believed the motif of the long boat was a reflection of the

popular custom of boat racing in southern China. According to

Feng, the boat does not have an outrigger, thus, it could only

have been used in rivers or small inner waters like the Dian

Lake. Further, to decorate boats with birds was also an old

tradition in China. He also believed that the motif might

indicate some connections with the Chu. Ling Shunsheng, a

Chinese ethnologist, wrote in 1950 that the motif of the long

boat was a direct reflection of the custom of boat racing in

ancient Chu.[5?] Although legend has it that the custom was to

pay tribute to the memory of Qu Yuan, a Chu poet from the 3rd

century BC, Ling argued that the custom had an even earlier

origin.[57] Chinese scholars later pointed out that the boats

on bronze drums were involved in four different kinds of

activities which were all popular in ancient southern China,

namely, fishing, navigating, boat racing and offering

sacrifices to the spirits of the river.[58]

Vietnamese scholars later accepted the idea that the motif

was about boat racing. However, they interpreted it as a part

of the ancient Viet ceremony for seeking rain and water.[59]

Figure VI: Shining entities on bronze drums[60]

As for the shining entity located in the center of the

surface of the bronze drum, some scholars have interpreted

this as a star, while others have viewed it as the sun.

Vietnamese scholars have taken the position that this reflects

the ancient Viet custom of worshipping the sun.[61] Meanwhile,

Chinese scholars have argued that many ancient ethnic groups

in China, such as the Shang (or Yin), the Chu, and other

southern peoples, all worshipped the sun. Moreover, rulers

tended to use the sun as a symbol of themselves.[62]

The two most common geometric motiffs on bronze drums are

believed to represent clouds and thunder, respectively.

According to Chinese scholars, the same motifs can be found on

the ancient carved-motif pottery of southern China, as well as

the bronze wares of the Central Plain. "They [the motifs]

prove the uniformity and continuity of the cultural

development of ancient southern China and the frequent

cultural exchange between southern China and the Central

Plain."[63] They also reflect the custom of worshipping clouds

and thunder in ancient China. These motifs appear only

occasionally on Dong Son drums, but can be frequently seen on

Heger's type II drums, most of which have been found in

southern China, especially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous

Region. Vietnamese scholars did not openly object to the

Chinese claim that such motifs reflect Chinese influence,

however, they strongly rejected the idea that such an

influence proves that the bronze culture of the south

developed under Chinese influence, and that drums bearing such

motifs are the most ancient.[64]

In sum, Vietnamese scholars tend to view the decorations of

early bronze drums, especially the Dong Son drums, as a

reflection of the special cultural characteristics of the

ancient Viet people. They believe that the various motifs on

the bronze drum describe the various aspects of the life of

the ancient agrarian Viet culture of the Dong Son age.[65]

They therfore argue that the decorations prove that the Dong

Son drum belonged to the ancient Viet people. However, Chinese

scholars interpret the decorations as a reflection of the

cultural exchange between interior C?ina and China's frontier,

arguing that they represent the cultural features of the

various peoples living in that area, and not just the Lac

Viet. They do not deny the affiliation between the Dong Son

drum and the Lac Viet, but they believe the same type of drum

was also used by other ancient ethnic groups such as the Dian,

the Laojin, the Mimo, the Yelang and the Juding, who are

believed to be the relatives of the Lac Viet. They thus

contend that the earliest type drum was invented in a region

belonging to modern China. According to them, "the Dong Son

drum is a developed form of the imported Chinese Shizhaishan

drum, which spread from Yunnan to Vietnam along the Red

River."[66] Citing both historical records and archaeological

findings, Chinese scholars have tried to prove that the

earliest drum was invented by the Pu-Liao groups, which

included the Dian from the Dian Lake area of Yunnan, the Yeyu

and Mifei of the Chuxiong and Erhai areas of Yunnan, the

Yelang and Juding of western Guizhou, and the Qiongdu of

southwestern Sichuan. According to Chinese scholars, the

bronze drum was first invented by the Pu-Liao people on the

eastern Yunnan plateau, and then spread to the surrounding

areas.[67] Chinese scholars have proposed that the Lac Viet

also belonged to this Pu-Liao group, and have cited the

similarities between the Dian culture in Yunnan and the Dong

Son culture of Vietnam as evidence.[68] |

| Nationalism and the Bronze

Drum |

|

The functions and the molding methods of the bronze drum

also caused much controversy. However, these issues are less

related to the origins of the bronze drum, and hence,

differences on such issues have been more individual than

national. Only in regards to issues that are more relevant to

the ethnic and geographical origins of the bronze drum, such

as its classification, dating and the interpretation of the

decorations, can a clear national difference be discerned. In

fact, the issue of the origin of the bronze drum came to

resemble a sacred topic in both countries. The scholars in

each country debated freely among themselves about many

details. For example, there are Vietnamese scholars who

support the Chinese claim that the flying bird is a heron, and

Chinese scholars who believe that the bird is the totem of the

Lac people.[69] However, once the debate touched on the key

issue of origin, all scholars took a national stand.

Therefore, the Vietnamese scholars who support the heron

interpretation do not believe that there is a connection

between the heron and the Chinese spirit of the drum, while

the Chinese scholars following the Lac bird explanation do not

think it has anything to do with the Vietnamese origin of the

bronze drum. Hence, they have quarreled freely about the

smaller details, but no one has dared to challenge the larger

conclusions.

The origin of the bronze drum was deemed important by

scholars in China and Vietnam during this period of tim? not

only because of its academic significance, but also because of

its political value, with the latter probably outweighing the

former. To the Chinese and Vietnamese scholars, the bronze

drum was not just an archaeological artifact, but more

importantly, a crucial part of their national culture and

national identity. The sound of the ancient bronze drum

stimulated the modern nationalistic nerves of the

archaeologists.

Communist victory in China and Vietnam brought about a

process of reconstructing history in both countries, which was

guided by two important principles, Marxism and nationalism.

The research of sensitive topics concerning the past

relationship between the two countries, such as the issue of

the bronze drum, was always permeated by a strong

nationalistic spirit. When the two countries enjoyed

"comradeship plus brotherhood" (in Chinese, "Tongzhi jia

xiongdi") from the 1950s to the mid 1970s, that spirit was

covered with a Marxist internationalist coating. Hence, the

Vietnamese and Chinese scholars made their own nationalistic

claims but never openly accused each other. For example, both

Wen You and Dao Duy Anh published their works in the 1950s,

Wen was the first Chinese scholar to attempt to modify Heger's

classification to propose a China origin of the bronze drum,

while Dao made the claim that the bronze drum was invented by

the Lac Viet and then spread to some minority areas of

Vietnam, southern China and insular Southeast Asia. Their

works went unnoticed for about two decades. It was not until

the late 1970s that they were accused of mixing academic work

with chauvinist or nationalistic agendas. The break-down of

Sino-Vietnamese bilateral relations in the late 1970s brought

nationalism to the fore in both countries, thereby overriding

the internationalism of the previous years.

For Vietnamese scholars, an essential part of

reconstructing Vietnamese history was to prove the existence

of the legendary Van Lang state established by the Hung Kings,

which was in turn part of a larger program to prove that the

Red River delta was an early center of civilization

independent of the north. Their starting point was to

establish a direct relationship between the Hung Kings and

Dong Son culture, and then to prove that the Dong Son culture

was native to northern Vietnam. To do so, they had to prove

the native origin of the bronze drum because it is one of the

most important artifacts of the Dong Son culture. According to

Pham Huy Thong, who wrote the prefaces to the two special

issues on bronze drums in the journal Khao Co Hoc (Archaeology

) , "In our process of studying the dawn of human history,

namely, the age of the Hung Kings, the artifact that has

gradually emerged as the most deserving symbol of the Hung

Kings civilization is the bronze drum. More accurately

speaking, it is the type I drum among the four types

classified by Heger in the beginning of this century".[70] In

his work on the bronze drum published posthumously in 1990, he

declared that "the ?ong son drums were cast on Vietnamese soil

by the bearers of the Dong Son culture at the time of state

formation. They were the handiwork of the forebears of the

present-day Vietnamese, the ancient Viet state builders who

were conscious of their ethnic and cultural identity."[71]

According to Pham, the idea that the bronze drum was an

original and typical artifact of the Dong Son culture was

first brought up by the four-volume collective historical work

Hung Vuong Duong Nuoc (The Founding of the State by the Hung

Kings), published between 1969 and 1971, and that it had then

become the foundation on which all further studies of the Dong

Son culture were based.[72] A later book about how the Hung

Kings built the Vietnamese nation has a picture of a bronze

drum on its cover, and lists the bronze drum as the most

typical artifact of the Dong Son culture.[73]

For Chinese archaeologists, bronze drums served different

purposes at different times. For the older generation of

Chinese scholars like Luo Xianglin and Xu Songshi, not only

the Han Chinese, but also the various ethnic groups in

southern China, were all considered to be branches of the

larger Han Chinese race. They supported Sun Yat-sen's claim

that China had only five ethnic groups, namely, Han, Hui

(Muslims), Manchus, Mongols, and Tibetans. That classification

included most ethnic minorities in southern China in the Han

group.[74] Both Luo and Xu were southerners themselves. To

them, the bronze drum served as an indicator of the cultural

achievement of the southern Chinese as well as a symbol of

southern identity. After 1949, the Chinese government

officially identified many southern groups as ethnic

minorities independent of the Han, and it encouraged scholars

to prove that the minority peoples had their own cultural

achievements, and that historically there had been much mutual

influence between the Han Chinese and the Southern minorities.

As a result, the bronze drum, which was scorned by earlier

Chinese scholars because of its "barbarian" origins,[75] was

now regarded as one of the most magnificent material relics of

the southern minority peoples and the symbol of

interior-frontier cultural exchange. The Chinese archaeologist

Wen You wrote, "If somebody asks, what is the most important

ancient cultural relic of our minority siblings in southern

China, we can answer him unhesitatingly that it is the bronze

drum." The bronze drum, he further claimed, was the "common

treasure of all the people of China".[76] The two authors of

an article about the ethnic affiliations of the various types

of bronze drum concluded that their study "reflects in a

specific aspect the process of ethnic mixture and cultural

exchange among the brotherly ethnic groups of China," and

"sufficiently proves that the various ethnic groups in

southern China, together with other ethnic groups of China,

created the great, brillant ancient culture of the Chinese

nation."[77] Such expressions are very common among Chinese

archaeologists. Moreover, such research might also be related

? to the construction of local identities, and the expressions

of local pride, as evidenced by the subtle differences between

the Guangxi and Yunnan scholars on the issue of the origins of

the bronze drum.

The core issue is that both Vietnamese and Chinese scholars

try to make exclusive claims on a tradition that was possibly

shared by the ancestors of both the Vietnamese and the

minority peoples of southern China. There was no boundary

between southern China and northern Vietnam at the time the

bronze drum was invented. Many of the groups living in that

vast area were interrelated either biologically, culturally,

or both. The people who invented the bronze drum would have

had no consciousness of polities such as "Vietnam" or "China,"

as we do today. It is unfair to impose such modern concepts on

ancient peoples and to determine exactly when, where and who

invented the bronze drum. Charles Higham, an outsider to these

disputes, commented that the nationalistic bias of the

Vietnamese and Chinese archaeologists had obscured the

situation revealed by archaeology. He hypothesized that the

bronze drum was created by the specialized artisans of a

cluster of increasingly complex polities that spread across

the present day Sino-Vietnamese border to arm the warriors of

their polities and signal the high status of their leaders. He

concluds: "Seeking the origins of this trend and the

associated changes in material culture in one or other

particular region misses the point. Changes were taking place

across much of what is now southern China and the lower Red

River Valley by groups which were exchanging goods and ideas,

and responding to the expansion from the north of an

aggressive, powerful state."[78] Hence, the theme of the

bronze drum could equally make for an excellent story about

the cultural coprosperity and unity of the various peoples

living in that area.

It is interesting to note that in order to prove the

indigenous origins of the bronze drum (in either southern

China or northern Vietnam), both Vietnamese and Chinese

scholars have vehemently denied any possibility of a place of

origin outside of the present-day southern China and northern

Vietnam landmass. J.D.E. Schmeltz's (1896) theory about the

Indian origin of the bronze drum, A.B. Meyer and W. Foy's

(1897) theory about the Cambodian origin and R.Heine-Geldern's

(1937) theory about the European origins of the Dong Son

culture have all been criticised by both Vietnamese and

Chinese scholars.[79] In fact, this is probably the only

significant common ground for scholars from the two countries

about the origin of the bronze drum.

The obscurity of the information about the bronze drum is

an important element in the whole debate. There are no

inscriptions on the bronze drums. The records in Chinese

classics about the origins of the bronze drum are not

supported by solid evidence and are often contradictory.

Modern techniques have also failed to provide hard evidence

about its origin. As a result, neither side has been able?to

persuade the other. All conclusions made about the origin of

the bronze drum are more or less speculations, which are the

result of limited archaeological information and nationalistic

sentiment. In other words, the bronze drum is an artifact

ambiguous enough for both sides to render some meaningful

interpretation for themselves. The same ambiguity makes it

difficult for an outsider to determine who is right and who is

wrong.

Largely as a result of improved Sino-Vietnamese bilateral

relations, the crossfire between Chinese and Vietnamese

scholars over issues surrounding bronze drums has come to an

end. However, neither side has changed its stand. They have

just set the topic aside, or have made their own claims from

time to time without openly accusing the opposite side, a

situation similar to that which prevailed in the 1950s and

1960s. Hence, the issue has been suppressed but not solved,

and it will probably reemerge under new circumstances. There

may be more academic exchanges between Chinese and Vietnamese

scholars in the future, and more research on other aspects of

the bronze drum may take place as well. However, the views on

the origins of the bronze drum held by each respective side

are not likely to change in the near future, as it is the

result of a tradition that has existed in the two countries

for a long time-a tradition of making official history and of

using the past to serve the present. |

References:

[1]Zhongguo Gudai Tonggu Yanjiuhui, Zhongguo gudai tonggu

(The Ancient Bronze Drums of China), Beijing: Wenwu Press,

1988, 8. Hereafter, ZGTY. According to the book, the numbers

of bronze drums stored in various provinces and cities are as

follows: Guangxi: 560; Guangdong: 230; Shanghai: 230; Yunnan:

160; Guizhou: 88; Beijing: 84; Sichuan:51; Hunan: 27;

Shandong: 8; Hubei: 6; Zhejiang: 6; Liaoning: 4. The total

number of bronze drums stored in China remained unchanged in

1995. See Xin Hua News Agency, "Nanfang tonggu wenhua yanjiu

you chengguo" (Results have been achieved in the Study of the

bronze drums of southern China), January 12, 1995.

[2]Nguyen Duy Hinh, "Bronze Drums in Vietnam," The Vietnam

Forum, No. 9 (1987) : 4-5; Pham Huy Thong, Dong Son Drums in

Vietnam, Hanoi: The Vietnam Social Science Publishing House,

1990, 265. Some more Dong Son drums have been found in Vietnam

since then. For example, in 1994, a Dong Son drum later named

a Ban Khooc drum was found in Son La Province in northwestern

Vietnam. Pham Quoc Quan and Nguyen Van Doan, "Trong Dong Son

La" (The Son La Bronze Drum), Khao Co Hoc, No.1 (1996):10.

[3]Xu Songshi, Baiyue xiongfeng lingnan tonggu (The

Masculine Spirit of the Hundred-Yue and the Bronze Drums of

Southern China), Asian Folklore & Social Life Monographs

95, Taibei: The Orient Cultural Service, 1977, 7-8)

[4]Nguyen Duy Hinh, "Trong dong trong su sach" (The Bronze

Drums in Historical Records), Khao Co Hoc, No. 13

? (1974):18-20.

[5]Jiang Tingyu, Tonggu shihua (History of the Bronze

Drum), Beijing, Wen Wu Press, 1982, 18.

[6]For a comprehensive introduction to and list of Western

archaeological works on the bronze drum, see, Pham Minh Huyen,

Nguyen Van Huyen & Trinh Sinh,Trong Dong Son (The Dong Son

Drums), Hanoi: Nha Xuat Ban Khoa Hoc Xa Hoi, 1987, 12-14;

306-309; ZGTY, 10-12.

[7]Wenwu Bianji Weiyuanhui (Editorial Board of Cultural

Relics), Wenwu kaogu gongzuo shinian: 1979-1989 (A Decade of

Work in the Field of Cultural Relics and Archaeology:

1979-1989), Beijing, Wenwu Press, 1990, 376;380.

[8]Pham

Minh Huyen et al..

[9]Pham Minh Huyen et al., 19-21; ZGTY, 10-11.

[10]Pham Minh Huyen et al., 21-22.

[11]Tran Manh Phu, "Thu chia nhom nhung trong dong loai I

Hego phat hien o Viet Nam" (The Classification of Heger's Type

I Bronze Drums Discovered in Vietnam), Khao Co Hoc, No. 13

(1974): 83-94.

[12]Luu Tran Tieu & Nguyen Minh Chuong, "Nien dai trong

Dong Son" (The Dating of the Dong Son Drums), Khao Co Hoc, No.

13 (1974): 117-121.

[13]Chu Van Tan, "Nien dai trong Dong Son" (The Dating of

the Dong Son Drum),Khao Co Hoc, No. 13 (1974): 106-116.

[14]Diep Dinh Hoa & Pham Minh Huyen, "Ve viec chia loai

trong loai I Hego va moi quan he giua loai trong nay voi cac

loai trong khac" (The Classification of Heger's Type I Bronze

Drums and Its Relationship with Other Types of Bronze Drum),

Khao Co Hoc, No. 13 (1974) :126-134.

[15]Pham Minh Huyen et al., 23-34; 120-123.

[16]For example, Heger's type II were mostly found in

southern China and among the Muong minority of Vietnam; type

III existed in Burma and southern China but not in Vietnam;

type IV were believed to exist in southern China only.Pham Huy

Thong, "Trong Dong" (The Bronze Drum), Khao Co Hoc, No.

13(1974): 9-11. It was reported in the 1980s that 14 type III

drums and 6 type IV drums had been found in Vietnam. Nguyen

Duy Hinh, 4.

[17]ZGTY, 12.

[18]Wen You,Gu tonggu tulu (Collected Pictures of the

Ancient Bronze Drums), Beijing: Zhongguo gudian yishu Press,

1957; Huang Zengqing, "Guangxi tonggu chutan" (The Bronze

Drums of Guangxi), Kaogu, No. 11 (1964); Hong Sheng, "Guangxi

gudai tonggu yanjiu" (The Ancient Bronze Drums in Guangxi),

Kaogu Xuebao, No. 1 ( 1974 ): 45-90.

[19]Quoted from Li Weiqing, "Zhongguo nanfang tonggu de

fenlei he duandai" (The Classification and Dating of the

Bronze Drums of Southern China),Kaogu, No. 1 (1979): 66-78.

[20]Wang Ningsheng, "Shilun zhongguo gudai tonggu" (On the

Ancient Bronze Drums of China),Kaogu Xuebao, No.2 (1978). In

Wang Ningsheng, Minzu kaoguxue lunji (Collected Eaasys on

Ethnoarchaeology), Beijing: Wenwu Press, 1989, 277-306.

[21]Li Weiqing, 66-78.

[22]Shi Zhongjian, "Ancient Bronze Drums," China Pictorial,

No.10 (1983):24-25.

[23]Wen You worked in Sichuan as a University professor for

? more than ten years before he moved to Beijing in the

mid-1950s. He wrote in 1956 that he first became interested in

the bronze drum when he saw a beautiful bronze drum in Hanoi

more than a decade earlier. Wen You, preface.

[24]Shi Zhongjian, "Shizheng Yue yu Luoyue chuzi tongyuan"

(On the Common Origin of the Yue [Viet] and Luoyue [Lac

Viet)], in Baiyue minzushi yanjiuhui, ed., Baiyue minzushi

lunji, Beijing: China Social Science Press, 1982, 203.

[25]Xin Hua News Agency, 1995, 1,12.

[26]ZGTY.

[27]Pham Huy Thong (1990).

[28]ZGTY; Pham Huy Thong (1990).

[29]Fan Chengda, a scholar-official of the Song Dynasty

(960-1279 AD) first suggested that the bronze drum was

invented by Ma Yuan. A scholar in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644)

first recorded that the big bronze drum was invented by Ma

Yuan, and the small one by Zhuge Liang. F. Hirth tried to

prove these stories in two articles published in 1898 and

1904. Zheng Shixu (Cheng Shih-hsu),Tonggu kaolue (A Study of

the Bronze Drum), Shanghai: Shanghai Museum, 1936, 3-5; 14;

33-37. Today, however, nobody follows these ideas anymore.

[30]Nguyen Duy Hinh, "Ve guan diem cua mot so hoc gia Trung

Quoc nghien cuu trong dong nguoi Viet" (A Review of the Views

of Some Chinese Scholars on the Bronze Drums of the Vietnamese

People), Khao Co Hoc, No. 4 (1979): 17-19.

[31]Nguyen Duy Hinh (1979), 21; Chu Van Tan, "Phai chang ho

da tim thay trong X?"(Have They Discovered Drum X?), Khao Co

Hoc, No. 9 (1982): 33.

[32]Pham Huy Thong (1990), 269.

[33]Tong Enzheng, "Shilun zaoqi tonggu" (On the Early

Bronze Drums), Kaogu Xuebao, No. 3 (1983). In Tong Enzheng,

Zhongguo xinan minzu kaogu lunwenji (Collected Essays on the

Ethnoarchaeology of Southwestern China), Beijing: Wenwu Press,

1990, 163-185.

[34]Nguyen Van Huyen, "Tu chia loai nhom den tim hieu nien

dai va que huong cua trong dong co" (From the Classification

and Sub-classification of the Ancient Bronze Drums to the

Understanding of their Dating and Origins), Khao Co Hoc, No.

13 (1974); Chu Van Tan 91974).

[35]Diep Dinh Hoa & Pham Minh Huyen.

[36]Luu Tran Tieu & Nguyen Minh Chuong.

[37]Pham Minh Huyen et al., 1987:216-217.

[38]ZGTY, 110.

[39]Wang Dadao, "Yunnan qingtong wenhua jichi yu Yuenan

Dongshan wenhua, Taiguo Banching wenhua de guanxi" (The Bronze

Culture of Yunnan and its relations with the Dong Son Culture

of Vietnam and the Ban Chiang Culture of Thailand), Kaogu ,

No. 6 (1990), 536;540.

[40]Chu Van Tan (1982), 30;32.

[41]Quoted from Dao Tu Khai, "Chim Lac hay con co? Ngoi sao

hay mat troi?"(Lac Bird or Heron? Star or Sun?), Khao Co Hoc,

No.14 (1974 ): 27.

[42]Dao Tu Khai, 27.

[43]Vu The Long, "Hinh va tuong dong vat tren trong va cac

do dong Dong Son" (The Motifs and Figurines of Animals on

Drums and Other Dongsonian Bronze Artifacts), Khao Co Hoc, No.

14 (1974): 9.

[4?]Dao Tu Khai, 28-29.

[45]Taylor Keith Weller,The Birth of Vietnam, Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1983, 7;313.

[46]ZGTY, 157.

[47]ZGTY 1988:233.

[48]Pham Huy Thong (1990).

[49]Wen You.

[50]ZGTY, 160-161.

[51]Schafer Edward,The Vermilion Bird, Berkeley: University

of California Press, 1967, 254.

[52]Vu The Long, 17.

[53]Pham Huy Thong, (1990), 268.

[54]Tong Enzheng, 178.

[55]Quoted from Chen Guoqiang, Jiang Binzhao, Wu Mianqi

& Xing Tucheng, eds., Baiyue minzu shi (A History of the

Hundred-Yue), Beijing: China Social Science Press, 1988, 335.

[56]Feng Hanji, "Yunnan jinning chutu tonggu yanjiu" (A

Study of the Bronze Drums of Jinning, Yunnan),Wen Wu, No.

1(1974): 56-58.

[57]Ling Chunsheng, "Ji benxiao er tonggu jianluan tonggu

de qiyuan he fenbu" (On the Two Bronze Drums Stored at

National Taiwan University and the Origin and Distribution of

the Bronze Drums),Guoli Taiwan daxue xuebao, No. 1 (1950).

[58]ZGTY, 175-181.

[59]Pham Minh Huyen et al, 239.

[60]ZGTY, 152.

[61]Dao Tu Khai, 30.

[62]ZGTY, 151.

[63]ZGTY, 154.

[64]Nguyen Duy Hinh (1979), 23.

[65]Tran Quoc Vuong, "Trong dong va tam thuc Viet co" (The

Bronze Drum and the Mentality of the Ancient Viet People),

Khao Co Hoc, No. 3 (1982): 25; Dao Tui Khai, 28-29.

[66]ZGTY, 127-129.

[67]Wang Ningsheng, 305; Tong Enzheng, 181.

[68]Tong Enzheng, 173-174.

[69]Shi Zhongjian (1982), 194.

[70]Pham Huy Thong, "Trong Dong" (The Bronze Drum), Khao Co

Hoc, No.13 (1974), 9.

[71]Phan Huy Thong (1990), 262.

[72]Phan Huy Thong (1990), 264.

[73]So Van Hoa-Thong Tin Vinh Phu, Cac Vua Hung da co cong

dung nuoc..., Tap luan van ky niem 30 nam nhay Bac Ho den tham

Den Hung: 19-9-1954--19-9--1984. (The Hung Kings have

contributed to building our nation), Vinh Phu, 1985.

[74]Luo Xianglin, Zhongxia xitong zhi Baiyue (The

Hundred-Yue as a Branch of the Chinese Race), Chongqing: Duli

Press, 1943, 1-2; Xu Songshi, 96-97.

[75]For example, Wen You lamented that traditional Chinese

scholars before the Qing dynasty seldom paid serious attention

to the bronze drum because it did not have inscriptions and

that it was made by the "barbarians." During the Qing dynasty,

However, more attention was paid to the bronze drum and

several books were produced. Wen attributed this to the myth

about Ma Yuan and Zhuge Liang creating the bronze drum that

gradually became popular in China after the Song dynasty. Wen

You, preface.

[76]Wen You, preface.

[77]Li Weiqing & Xi Keding, "Shi tan zhong guo nan fang

tong gu de zu shu" (An Inquiry into the Ethnic Affiliations of

the Bronze Drums of Southern China) in Xi nan min zu yan jiu

(Studies on the Ethnic Gr?ups of Southwestern China), Chengdu:

Sichuan Minzu Press, 1983, 427.

[78]Higham Charles,The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996, 134.

[79]ZGTY, 10-11; Pham Huy Thong (1990), 263-264. |

Dr. Xiaorong Han teaches at the University of Hawaii-West

Oahu. His research interests include: Peasants and Ethnic

Minorities, Modern China and Southeast Asia; Nationalist and

Communist Movements, Modern East and Southeast Asia;

Sino-Vietnamese Relations: Past and Present; General and

Comparative History, East and Southeast Asia.

|

|